Woodcarver Ezine

Back Issues

Carvers' Companion Gateway

|

I imagine that we have all heard statements such as "paint covers up bad carving" or "sanding is a crutch for carvers who can't make clean cuts." Maybe in a few cases that's true, but let me suggest a different slant on the subject. Bear with me for a little history.

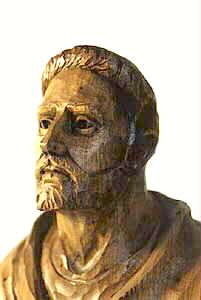

In the Middle Ages most wood statues were painted. Wood was considered simply a base material whose chief asset was its workability and its absorbancy in accepting gesso and paint. Carvings to be polychromed were intentionally left rough and with a minimum of detail in order to create a better bond with the gesso. Often the finer details were created by building up forms--veins, eyebrows, small decorative details--in the plaster and gesso, not in the wood.

|

That started to change (sometime before 1500), notably with the sculptures of the legendary Riemenschneider. He often chose monochromy (glazing his carvings with a single color) over polychromy. A brilliant carver, this allowed him to emphasize the wood and show his mastery of it. Rather than leaving the surfaces rough to accept the gesso and the paint, he was now able to use his exceptional carving techniques to work the surfaces in many creative ways, leaving some areas smooth for one effect and making them textured for another, much of which would have been pointless had the carving been polychromed.

With carvers such as Riemenschneider, then, wood sculpture began to emphasize the carving skills over the painting skills of the artists. The carving was not merely the foundation for a "painting in the round," the wood itself was the most important element in the end result.

Further, with the acceptance of wood an an appropriate material for art, the woodworking skills--as oppoased to the painting skills--of the artist became dominant. Because they were no longer hidden by paint, cutting techniques were highlighted as tools were worked in various ways to create the surface interest, the light and shadow, that color had created before. These techniques formed the "palette" of the wood carver: texturing a surface to create low light; smoothing a surface to create highlingt; "throwing the light around" by carving facets--as in a diamond--to create an interesting play of light on the surface of the wood.

|

Understandably, certain schools of carving also discouraged the use of abrasives, not necessarily because it was a cop-out, but because sanding rounds off the fine edges of the forms and erases the facets that make the surface sparkle. If one believes, as one carver expressed, "every square inch of a carving should be interesting," one would not want to sand away the very tool cuts that help create that interest.

Thus, the point isn't so much that paint is rejected by some schools of carving because it "covers up bad carving" (It can just as easily cover up GOOD carving), or that "sanding is a crutch," the real point is that carvers who choose not to paint or sand their carvings are simply continuing the legacy of those who have placed their emphsis on the wood itself and on the specific techniques that traditionally have been used to show off wood's unique character as an art medium.

Some splendid sculptures are painted. Some splendid sculptures are sanded. Many carvers, however, choose to do neither as a way of continuing a tradition, where nothing covers up the wood or obliterates the tool cuts and the play of light and shadow they create.

Ivan Whillock